Hummingbird Systematics (2004-2014)

Phylogenetic methods are among the most important tools in comparative physiology. Evolution provides natural experiments for traits of interest such as body size, diet, habitat, performance, and behavior. Hummingbirds are particularly useful organisms for studying the biomechanics and neural control of flight not only because of their extraordinary abilities, but also because they are one of the most diverse avian families with over 320 species. Hummingbirds vary in body size by an order of magnitude and live in a variety of challenging habitats including high elevations (up to 5000 m), extreme latitudes (from 55°S to 61°N), arid deserts, and tropical rainforests.

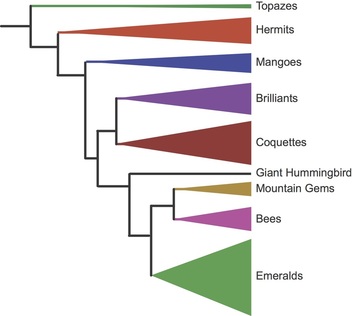

We participated in a collaborative effort led by Jim McGuire (UC Berkeley) to generate a comprehensive phylogenetic hypothesis for hummingbirds with dense taxon sampling. The first analysis (Altshuler et al., 2004) involved two nuclear and one mitochondrial gene for 75 ingroup (hummingbirds) taxa and one outgroup (swift) taxon. This work confirmed the placement of most of the major lineages proposed from a previous study by Rob Bleiweiss and colleagues (1997), but also led to the discovery of a novel clade of basal hummingbirds (Topazes) and a unique evolutionary position for the giant hummingbird (Patagona gigas). The next study (McGuire et al., 2007) expanded the analysis to four genes for 151 hummingbirds to conduct a phylogeographical analysis, which revealed that hummingbirds originated in the South American lowlands and that there have been at least 30 independent invasions of other primary landmasses. In an additional paper, we proposed a formal phylogenetic taxonomy for hummingbirds (McGuire et al., 2008).

The most recent work presented a phylogenetic hypothesis for 284 species and 436 exemplars based on DNA sequences from six genes (McGuire et al., 2014). This rich sampling allowed for resolution of the deepest splits within the hummingbird clade, and indicated that the speciation rate for hummingbirds remains high. Although we are no longer actively working in systematics, we continue to use phylogenetic hypotheses to explore the functional biology of hummingbirds and other clades of flying animals.